Affiliation:

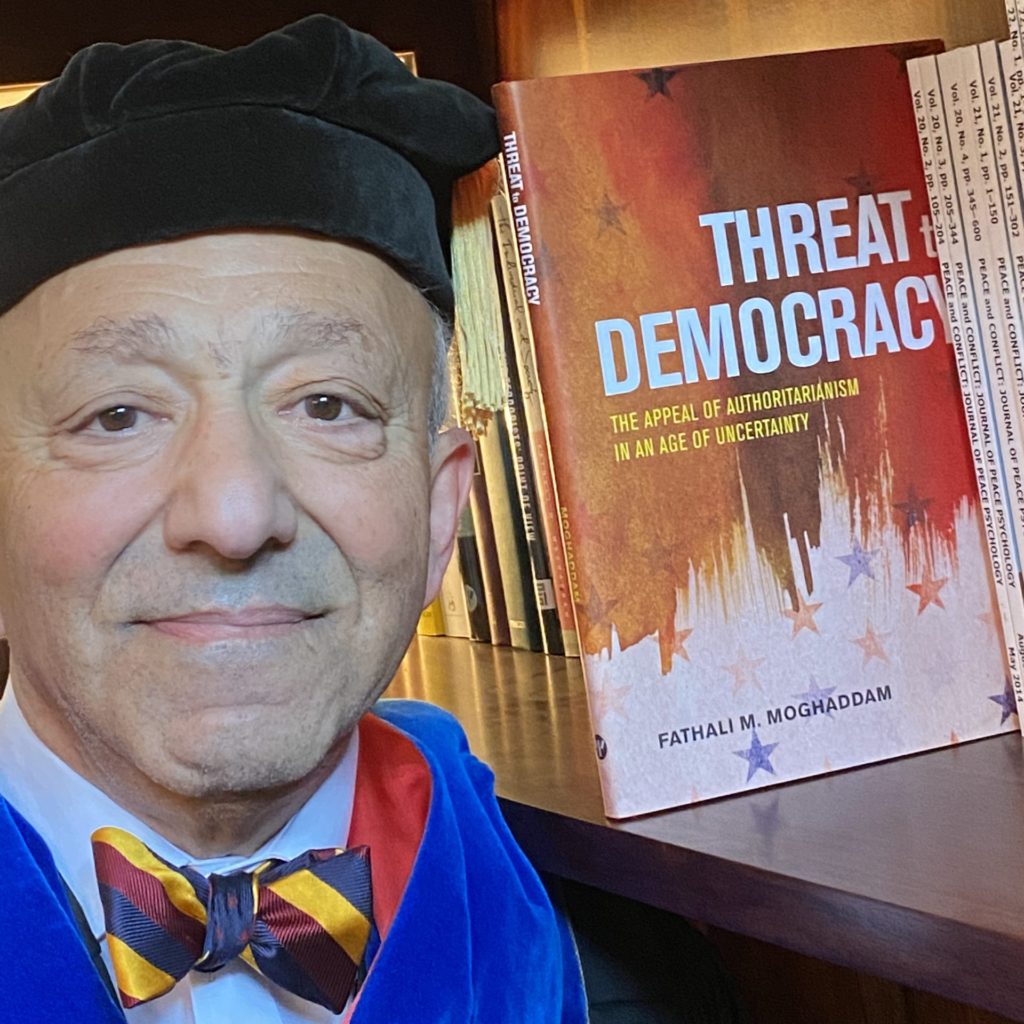

Georgetown University

Short bio:

Fathali M. Moghaddam is Professor of Psychology at Georgetown University. He was born in Iran, received his formal education in England, and worked for the United Nations and McGill University before joining Georgetown University. His research explores the psychological foundations of democracy and dictatorship, mutual radicalization, political plasticity, and causal and normative interpretations in psychological science. He edits theProgressive Psychology book series published by Cambridge University Press. His three most recent books are ‘The Psychology of Revolution’ (2024), ‘Political Plasticity’ (2023), and ‘How Psychologists Failed’ (2022).

Title:

The Psychology of Revolution

Abstract:

Although psychological processes play a central role in revolutions, psychologists have almost completely neglected this topic; there has been minimal psychological research on revolutions and the last scholarly book entitled ‘The Psychology of Revolution’ was published in 1894 (by Le Bon). I report on newly published research (The Psychology of Revolution, Moghaddam, 2024), which uses psychological theories and empirical research to examine the French, Russian, Chinese, Cuban, and Iranian Revolutions. I first examine processes leading to collective mobilization, the tipping point in regime collapse, and regime change. However, I argue that from a psychological perspective even more important than regime change is what happens after the new revolutionary government takes control. The concept of political plasticity guides us to better understand the post-revolution period. First, immediately after the revolution moderates are sidelined and power is grabbed by extremist leaders who are characterized by pathological narcissism, craving for power, risk-taking, Machiavellianism, intolerance for ambiguity, illusions of control and grandeur, and charisma. Second, radical revolutionaries attempt to bring about mass behavior change in line with their avowed revolutionary goals. Collectivization and other examples of revolutionary programs are used to illustrate how behavior change proves extremely slow in domains of low political plasticity. Third, perpetual revolution is attempted by some revolutionaries, through cultural revolutions and other radical programs, in attempts to force mass behavior change in the direction of their revolutionary goals. Fourth, in line with empirical evidence and historical case studies, revolutions resulting in absolute power transform into corrupt and repressive dictatorships. But despite revolutions being rare in history and bringing enormous hardships for many, certain shared illusions are still likely to motivate people to participate in future revolutions. The illusion-motivation model of revolution captures the power and direction of these shared collective and individual illusions.